Today’s stack is a little smaller than usual: a two-volume comic book biography, but it’s one that gave me a lot to think about.

Before we dive into the books, a little bit of personal background: I was born and raised in the US by immigrant parents, both of whom were born in mainland China (though in different cities), moved to Taiwan during childhood, and then came to the US for graduate school (where they met). Many of the Chinese-American adults I knew growing up had similar stories, with families that had moved to Taiwan during China’s civil war. I had relatives in Taiwan so we visited occasionally, and I had a vague understanding of the relationship between the Republic of China (located in Taiwan) and the People’s Republic of China (located on the mainland), but I didn’t know much about the history of Taiwan before the flood of mainlanders that started in the late 1940s. Mostly, as a kid, I absorbed a simplistic “ROC good, PRC bad” take on the situation, and it wasn’t until later that I learned enough to have a more nuanced take. Even then, it’s a complicated situation, as evidenced by the way the whole world dances around the politics of China and Taiwan.

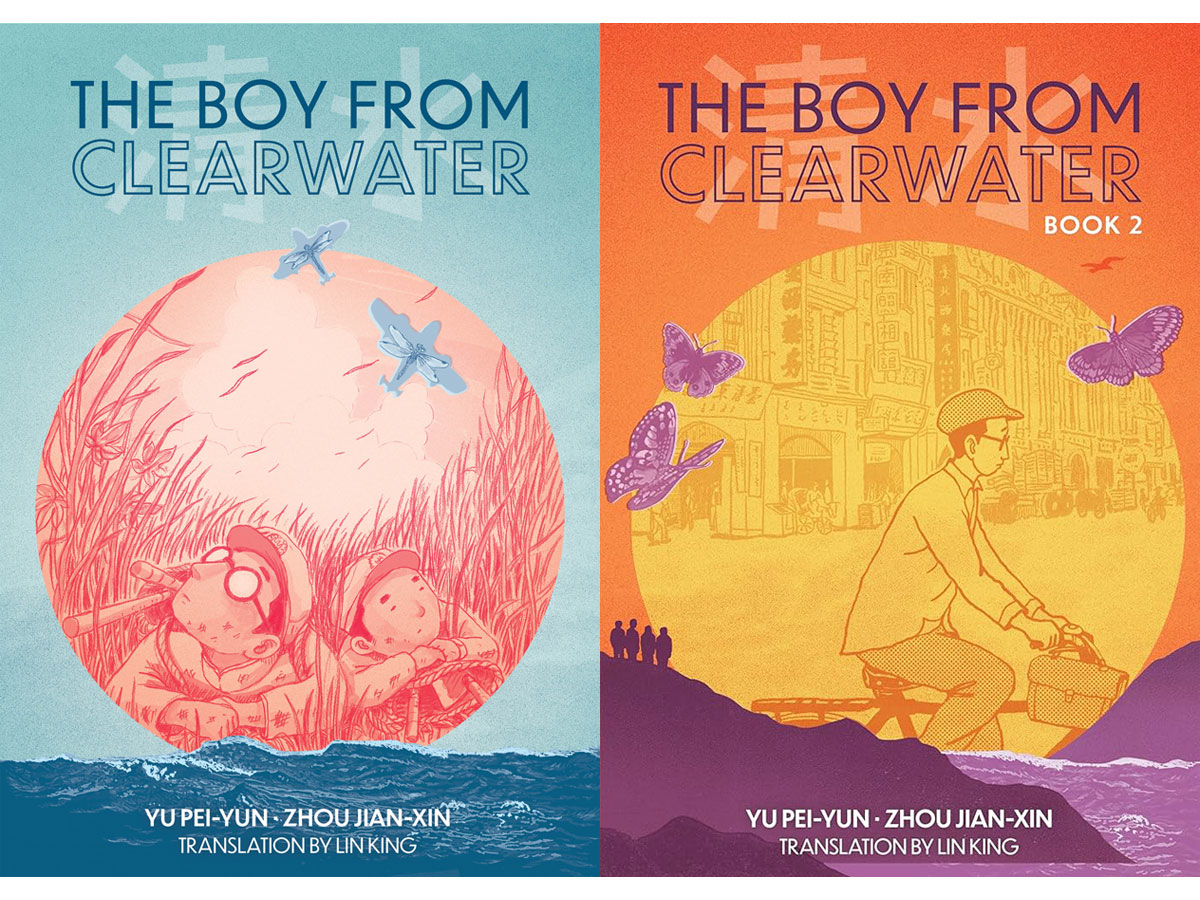

The Boy from Clearwater written by Yu Pei-Yun, illustrated by Zhou Jian-Xin, and translated into English by Lin King

These two comics tell the story of Tshua Khun-lim (also known by his Mandarin Chinese name, Tsai Kun-lin), who was born in 1930 in what is now Qingshui, Taiwan. Khun-lim lived through this extremely tumultuous period of Taiwan’s history, and personally experienced enormous losses and suffering because of the political turmoil, so his life serves as a valuable lens into this world.

The book opens with a brief history, explaining that Taiwan had been under Japanese control since 1895, so although many of the people spoke Hoklo Taiwanese at home, school and official business was conducted in Japanese, so many people often switched between the two (which is highlighted by different colors of text in the book). Students were given military training and worked for the Japanese Imperial Army; during World War II, Khun-lim and his fellow student soldiers considered themselves part of Japan.

But after the war, Japan returned Taiwan to China, which led to some significant changes: Mandarin Chinese was adopted as the national language, and many of the places that had Japanese names for so long were given Chinese names instead. The Kuomintang government of China worked to supplant 50-year-old Japanese culture on the island with mainland China’s culture through education, youth camps, and more. The influx of waishenreng (people from the mainland) would only increase with China’s civil war when the KMT government itself retreated to Taiwan, and there were a lot of tensions between the new immigrants and the Taiwanese population, including the 228 Incident in which tens of thousands of Taiwanese civilians were killed by government agents in an uprising.

It doesn’t take long for the KMT to start hunting down their perceived enemies, and Khun-lim is arrested at age 20—he’s accused of being a communist agitator because of a book club he joined in high school, and after being tortured and forced to sign a confession, is eventually sentenced to ten years of imprisonment on Green Island, a small island off the coast of Taiwan.

The first book covers Khun-lim’s childhood and school days, and then his time at Green Island. The second book picks up with Khun-lim restarting his adult life at age 30. The illustrations in the book shift in style over the course of the books. The first section looks like pencil illustrations and has a softer tone, but when he is arrested and sent to Green Island, they look like woodcuts, with jagged edges and a nervous energy to them. The third section, when Khun-lim gets into comics publishing (among other things), have a more graphic quality to them, before returning to something more like the first style for the conclusion of the second book.

The books paint a much bleaker picture of the ROC than the one I’d grown up with. I remember visiting the Chiang Kai-Shek Memorial Hall in Taipei, an enormous plaza that includes a huge statue that reminded me of the Lincoln Memorial. I had no reason to believe that Chiang Kai-Shek wasn’t seen as a hero, somebody who ushered in a new, prosperous era. I grew up in the ’80s, so Communist China was bad and democractic Taiwan was good, right? It turns out this era has another name that I’d never heard before: White Terror, encompassing over four decades after Chiang Kai-Shek declared martial law in 1949. Political rivals and suspected spies were imprisoned or executed, and as evidenced by Khun-lim’s own story, many of the accusations were baseless.

When Khun-lim is finally released (in book 2)—an outcome that was far from certain, as it turns out—he has trouble getting a job because people are afraid to employ somebody who has a criminal record. Even so, he experiences some successes, and then some tragic losses, and then more successes. His story isn’t easy to read: it feels like he has to start from scratch over and over again, but his determination and resilience pay off.

It isn’t until the ’90s, after the Tiananmen Square Massacre, that Taiwan’s government acknowledges the 228 Incident and allows it to be included in history books, and the late ’90s when those that were accused of sedition and espionage during the White Terror were finally given a chance at reparations. When Green Island is turned into a memorial park, Khun-lim becomes a lecturer there. His memories are a first-hand account of the injustices suffered by so many.

Reading these books was a hard reminder that history is written by the victors. Just like the rosy pictures of the US’s founding fathers that I learned in elementary school, my images of the ROC in Taiwan had been sanitized and carefully crafted. I’m glad that books like this one are helping to reveal a bit of what had been hidden away and censored, and it seems that Khun-lim—who died last year at the age of 93—was able to achieve some of his dreams and had his reputation restored, even though it took so long. It’s a powerful story and one that I’m really glad I read, even though it raised some uncomfortable questions about my own heritage and family history, and I’m planning to explore these topics more in the future.

My Current Stack

I just finished reading The Cautious Traveller’s Guide to the Wastelands by Sarah Brooks and thoroughly enjoyed it, so I’ll tell you more about that one soon. I also read a comic book called 8 Billion Genies by Charles Soule and Ryan Browne, which starts with a curious premise: what if every person on Earth suddenly and simultaneously had a genie that would grant them a single wish? It’s pretty fascinating and filled with chaos. More on that soon, too!

Disclosure: I received review copies of these books. Affiliate links to Bookshop.org help support my writing and independent booksellers!